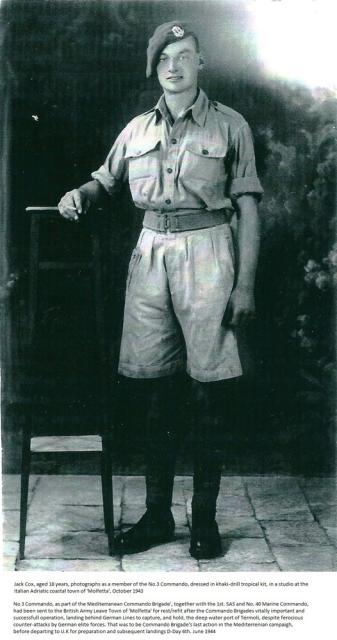

COX, Jack, An account of ops at Termoli

I was a member of 6 Troop No 3 Commando for this operation and we landed at 2am in pitch black darkness to form a bridgehead for the rest of the Brigade to come through. No 3 by then were desperately under-strength due to heavy casualties a few months previous and numbering at this time just under 200 out of an original strength of 450. The SAS were roughly in the same boat because of their own previous heavy casualty loss. 40 RM Cdo were however up to full strength and were to spearhead the attack on Termoli town and harbour. The SAS had their target to see to south of Termoli -whilst No 3, when their bridgehead was no longer required, would support 40 in their attack on Termoli.

Once No 3 were ashore, which was unopposed, to form a bridgehead, Cpl Jack Winser of 6 Troop [more...], in the pitch darkness, fell down a small cliff severely damaging his ankle, so he could not walk unaided. When it was ready for No 3 to move off from the bridgehead, I was detailed off to be Jack’s helper, with orders to follow on as best we could which we did in slow hobbling fashion, well behind No 3 who set off at a smart pace to support 40 Commando. Up to that stage the enemy were still unaware of the Brigade’s presence on land north of Termoli. As a direction guide Jack and I discovered the railway line, which, as stated in the briefing, led straight to Termoli and we duly followed it to come across a silent stationary steam train with carriages on the track. We learned later that 6 Troop had previously boarded the train, which was getting steam up and ordered the burning coals in the fire box to be raked out and then discovered a number of German soldiers asleep in the carriages and promptly took them all prisoners. Suddenly the still of the night was shattered by the sound of battle Royal, with fast firing spandau machine-guns sounding off. Also the slower chattering of Bren guns together with multi rifle fire - the sure sign the enemy had wakened to find Commandos on their doorstep. This caused Jack Winser and I to increase our hobbling considerably to eventually join up with No 3 in the outskirts of the town where Arthur Evans, a former policeman [more....], had just wiped out a Jerry spandua which had been sweeping murderous fire from an upper window of a warehouse. With a second attempt direct hit with a 36 Mills Grenade fired from the discharger cup fitted to his Lee-Enfield rifle, to the delight of 6 Troop, enabling them to get further into the town to support 40 Commando who were doing a good job against stern resistance by German Paratroops. We of 6 Troop were then detailed off to give covering fire to 3 Commandos Mortar Section as they engaged the crew of a German Artillery piece causing them to surrender by salvos of mortar bombs.

A short time later our 6 Troop sub-section, led by Sgt Nobby Knowland [more...], was withdrawn from the town where a number of the enemy who well positioned amongst small trees on a rise in the ground, were keeping up a hail of fire towards the town. To the front of the enemies position, some 80 yards distant, was a low dilapidated stone wall. Sgt Knowland ordered that we make a lightening dash to get behind that stone wall which we promptly achieved spreading our sub-section along the length of the wall, at the same time attracting enemy fire which we returned with interest. Sgt Knowland shouted a briefing to the sub-section that we would make a frontal assault on the enemy and to keep well spread out on the run in. He then ordered the Bren-gunner Jack Leech [more....] to get out to the left flank and give covering fire for our frontal attack. Jack managed that quickly and once his Bren was up, at Sgt Knowland’s intimation our whole sub-section, as a single unit, making ourselves as small as possible, quickly got over the wall flattening ourselves on the other side, amongst a hail of enemy bullets in our direction. The Sgt then gave the order ‘Go!’ And we leapt to our feet and made a steady run-in at the enemy position firing our rifles from the hip as we did so. The nearer we got to the enemy the fewer shots that came at us. Within 20 yards or so from the trees on the hillock all seemed silent from the enemy’s position so we all hit the ground to weigh up what was going on. The Sgt then ordered the right hand man, which happened to be me, to go forward to check the situation. All I saw were a number of German soldiers lying face downwards without any movement. I signalled the OK and the subsection got to their feet to run over the enemy’s position, to see 12 German Paras all lying apparently dead. We discovered 2 were still alive, one severely wounded in his leg and around his knee and in great pain. Another, a large man who had been feigning dead, got to his feet with tears running down his face sobbing uncontrollably; he was taken prisoner. Once Medical orderlies arrived we had difficulty lifting the wounded German on to a stretcher, every time we lifted him he screamed in pain. He was eventually taken away on a stretcher. By this time the battle for Termoli and harbour had been won.

About 70 German Paratroops were taken prisoner who turned out to be of the ‘Herman Goering’ unit who battled against No 3 Commando in Sicily a few months previous. Some of No 3 recognised amongst the prisoners Germans who had been their captors in Sicily until they eventually managed to escape to rejoin No 3. The atmosphere was friendly and animated conversations took place each side relating their experiences since Sicily. The Germans had given good treatment to our lads when prisoners in Sicily, accordingly the opportunity was not lost to repay the compliment. As always the German Paras fought bravely with stern resistance in the fight for Termoli, but the Commando fond strategy of ‘element of surprise’ by attacking at night when the enemy was least prepared, undoubtedly disadvantaged the German Paras in this Termoli battle.

We then had to dig in on countryside outside Termoli town to prepare for possible enemy counter-attack, whilst German prisoners cleared battle areas of their dead. As digging my slit-trench I had a good view of German Paras burying their dead in deepish graves they dug. I saw that once a grave had been re-filled with soil, all Germans so engaged would then stand stiffly to attention, some words were spoken for a minute or so with great solemnity, before they turned their attention to the next soldier to be buried, and so on. That extra little ceremony after each burial showed deep respect for a fallen comrade and greatly impressed me. The particular ground where I had to prepare my slit-trench was hard work due to the obdurate nature of the soil which was more gravel than earth, preventing me creating a decent trench where excavated soil is heaped and compacted in depth on enemy side of the trench to provide a near bullet proof firing point. My efforts in this instance left me with just a heap of gravelly soil in the edge of the trench. A German prisoner from the burial party, checking for any undiscovered dead Germans, walking past my slit-trench suddenly stopped, pointed to the gravelly soil and in perfect educated sounding English said, “You would never get away with that in the German Army”, and then walked on. At first I was more annoyed at his infernal cheek, then saw the amusing aspect, it being a good war story to relate. I further contemplated the courageous fight-back the German Paras gave us in the battle for Termoli town, also the severe victorious Commando bashing we handed out to them, and didn’t begrudge him that sarcastic remark at my expense.

Later that day and night and into the next day a few of the units of the 8th Army’s 78th Division began to get through to us, which included some infantry from the Argyles and from the West Kents, some artillery, anti-tank guns, and a few Sherman Tanks. Early evening No 3 Commando were sent to dig-in on a ridge, which was covered with low growing olive trees, a mile or so outside of Termoli. We of 6 Troop occupied the extreme right flank of No 3 and below the ridge on our right was a troop of SAS, but due to the undulating terrain with its hilly rise and fall, I seldom had more than a glimpse of them from my trench, in their distinctive light blue shirts and cream/buff coloured berets. We were told a German Panzar Division was advancing on Termoli, to keep very alert, as a counter-attack would be with us shortly. We spent a freezing cold night on that ridge being clothed only in our tropical khaki drill army issue shirts and slacks, on ‘stand-to’ all night. During that night enemy shells were dropping on to our ridge and No 3 sustained some casualties, none of 6 Troop, indicating the enemy knew of our ridge positions.

As dawn broke, 5 October 1943, low flying Luftwaffe aircraft appeared strafing our positions with machine-gun fire with a deep furrow, missing my trench by just a few feet. The planes then swooped off to attack Termoli town and harbour. It then rained heavily and we learned later that the River Biferno flooded to sweep away pontoon bridges put out by the Royal Engineers, cutting off further very needed reinforcements from the rest of 78th Division, who were stranded the wrong side of the river. The shelling increased in intensity and a wave of enemy attack tanks and infantry occurred on our left, forward of the ridge, where 5 Troop were positioned, together with Argyle’s infantry. A few Sherman Tanks appeared to reinforce the left flank with one being hit and burst into flames. The tanks withdrew to 5 Troops positions and the heavy enemy fire at the tanks caused casualties in 5 Troop ranks, who were then withdrawn to No 3 Commando ridge positions. The Argyles who fought well, sustained heavy casualties also and had to withdraw leaving the left flank of our ridge exposed. Our 6 Troop positions on the right flank received horrendous accurate shelling and it was about this time our Troop Commando, Captain John Reynolds [more....] received multi-shrapnel wounds, but insisted on staying with us in 6 Troop’s position. Later, however, he was removed to Termoli for hospital treatment.

The intense shelling we received on that ridge for long periods at a time was very accurate, it was because Commandos were well dug-in that prevented large amounts of casualties. 6 Troop, in our trenches had to watch our front carefully as we spotted far distance away on the flat ground beyond the ridge, German tanks and infantry advancing towards Termoli, but a distance too far away as yet to engage them with rifle and Bren. We did however have 78th Div Vickers Medium Machine Gun (tripod type) on 6 Troop front capable of very accurate fire at long range, which opened up on the advancing German forces. With the intense accurate shelling still persisting, at one point I heard popular Corporal Ronnie Gower [more....] in a trench near to me groaning loudly, clearly in pain, and assumed he had received wounds from the shelling. But when I went to his aid, I found a whole tree had been blown down from shell fire on top of him as he lay in his slit-trench and he’d received a severe blow from one of it’s stout branches on to his lower spine, convincing him his back was broken. Sgt Nobby Knowland and I lifted the tree off Ronnie who soon recovered his usual cheerful self once finding he had sustained only an extremely sore back. One of the 78th Div anti-tank guns had been set up in 6 Troop’s lines near to my trench. After a particularly severe spell of accurate enemy shelling, the crew became very active speedily removing the firing block from their anti-tank gun, and as one, the crew cleared off from the ridge towards the rear, like scalded cats. I shouted that information to Nobby Knowland who replied, “I had noticed - we’ll advance 20 yards and dig-in, perhaps the shells will drop behind us.” And we of his sub-section did just that. To this day I’m convinced our ‘mini-advance’ was Nobby’s way of showing his contempt for the anti-tank crew for running away from the fight. With Sgt Nobby Knowland, actions spoke louder than words.

A Jerry attack in strength came on our right flank against the under-strength Troop of SAS. Because of the undulating hilly nature of the terrain below we couldn’t see much of what was going on, could only hear and guess who was what and where. We opened fire in the general direction we thought the enemy must be. I did spot two SAS lads stopping in their tracks as they were retreating and firing their rifles from the standing position at the attackers, before having to continue their retreat, being out-numbered, as it transpired, by masses of enemy infantry in the first wave of their attack on our right flank. The SAS retreat left our right flank completely exposed so 6 Troop had to re-organise our positions to cover, best we could, the extreme right flank of No 3 Commando, which meant digging-in once more in new positions. Jack Leech was enjoying himself firing at enemy tanks, some of which were on open ground below our ridge, the multi trees on top of the slope up to our position clearly caused their tank crews not to attempt the long slope to our ridge. Jack told me at the time that when he peppered the front of the tanks with a full magazine from the Bren (32 rounds) he was amazed to see the enemy tanks stop in their tracks, and on one occasion actually went into reverse, which chuffed Jack no end. Trouble was, however, Jack inevitably fast ran out of ammo for the Bren, and the extra bandoliers of 50 rounds we all carried on sea landing operations - because fresh supplies of ammo were not possible as a rule - had to be handed over to Jack. The downside of that was it left we riflemen later short of ammo, the upside was Jack Leech did a brilliant job as our sub-section Bren gunner.

With the reorganising of our slit-trench positions followed the retreat of the SAS on our right flank, the 78th Div Vickers machine gun was forward in the trees of our new positions and kept up a good rate of fire against the distant oncoming enemy infantry and tanks, with the Vickers ‘cone’ of rounds fired, falling around infantry ranks, which only a Vickers machine gun expertly handled could produce at long distance, clearly slowing up the distant second wave of the enemies advance, as the result, enemy artillery concentrated their shell fire on the Vickers machine gun position just forward of 6 Troops lines. Despite this, with shells exploding all around, the Vickers kept up its high rate of fire and from its position I could plainly hear cries of “more ammunition”, as the belt fed ammo was being used up at a fast rate. I recall well being filled with huge admiration for the courage of the Vickers machine gun crew, it seemed to me at the time that they would be winning medals for their sheer guts, their position being massively stonked by concentrated enemy shelling and they never seeking slit-trench protection, but just continued their non-stop high rate of fire at the advancing enemy. I discovered later that Corporal Harrison, of 2 Troop 3 Commando, on seeing at one stage the Vickers crew removing the guns cocking handle and attempting on two occasions to depart to the rear, he ordered them at gun point, with his Colt 45 automatic revolver to ensure they continued firing the Vickers, Corporal Harrison himself suffering from shrapnel wounds to the head and leg. The shouts of “more ammunition, more ammunition” being repeated over and again coming from Corporal Harrison (Peter Young’s book ‘Storm from the Sea refers). That was the situation on 6 Troop’s front until the advancing second wave of the enemy were near enough for us to engage them with rifle and Bren gun.

With our Troop Commander Captain John Reynolds a casualty, Lieutenant John Alderson [more....] took over as 6 Troop Commander. The first Jerry infantry attack on 6 Troops position occurred with a series of white Very lights in the direction of their advance up the long wooded slope leading to our ridge – Lieutenant Alderson positioned himself ahead of my slit-trench, half crouched behind a shell battered olive tree – his orders were not to open fire until he gave the order. I could see German infantry in great-coats advancing cautiously up the slope and had my rifle in steady aim at one of them, awaiting the order to open fire. The order came with enemy about 50 yards away, with Lieutenant Alderson – normally quietly spoken – shouting above the din of battle with shells exploding elsewhere – “Fire 6 Troop, fire, fire, fire” which we did, my targeted German falling backwards and sideways as my first shot struck him. The first firing Spandau machine-guns had also opened up onto our positions firing tracer rounds – possibly to intimidate giving away their positions, which Jack Leech took full advantage with his Bren not firing tracer by knocking out each Spandau in turn. Once we riflemen opened fire Jerry infantry went to ground undergrowth on the wooded slope; in the failing light I was reduced to just firing at enemy gun flashes. After the first attack enemy withdrew to reform; with whistles being blown by the enemy, they launched further attacks up the wooded slope with Lieutenant Anderson still controlling 6 Troops response from his battered olive tree position. With intense fire by rifle and Bren (I felt sure my rifle barrel was red hot) we held 6 Troop lines intact until these infantry attacks ceased which by then it was dark.

Former CO of 3 Cdo, Colonel Durnford-Slater (DSO & Bar) [more...] was acting Brigadier of our Commando Brigade for the Termoli operation. In his post-war book “Commando” he wrote, referring to 3 Cdo’s defence of that ridge: “The fighting raged. No 3 Commando still out in front were giving their finest performance of the war. Hammered by tanks, pounded by guns, attacked by infantry, left and bleeding on their flanks by retreat of another unit, they did not budge from their positions”.

6 Troop lines had again to be re-organised to ensure more solid defence of 3 Cdo’s might flank and we dug-in once again. Shortly afterwards ‘Pud’ Saunders, a Londoner and very useful amateur middle weight boxer, also a friend of mine, appeared out of the night at my split-trench, prodding with his rifle a tall bare headed unarmed German soldier, overcoat open at the front, with sheaf’s of army type toilet paper in his hand. I instinctively said to ‘Pud’ “That’s all we need – what are we going to do with him?” Pud replied, “Couldn’t help it – he just walked into our listening post.” The German later admitted at 3 Cdo HQ on the ridge that he was of the 16th German Panzer Division. The toilet paper indicated why the German had been wandering about unarmed: it was also indicated how near to our ridge positions the enemy were, having moved up under cover of darkness. It was not long before we could hear them talking, we also saw the red glow of cigarettes being puffed.

A Spandau machine gun opened up from our rear together with rifle fire. Nobby Knowland our Sgt calmly gave the order, “Watch your rear, engage enemy on sight” which we did with rifle and Bren. I was convinced at that stage we of 3 Cdo were surrounded by the enemy, completely cut-off on our ridge from the main body of Commando Brigade. We then received the order to cease fire to conserve ammunition and everyone to remain on ‘Stand-to’.

Over to the left flank of our ridge haystacks were well alight (ignited by shell fire) their huge blaze illuminating that area and two German stationary tanks were clearly visible with their big guns pointing ominously along the length of our ridge. Tank crews were on foot outside tanks consuming food from mess tins. To conserve ammo made sense as it was clear, come the dawn, enemy would attack and we would need all the ammo we had left, in this case about 40 rounds which would not last long in a fire fight. Jack Leech told me he had hardly anything left for his Bren.

I was 18 years of age, been a soldier since 16yrs (lied about my age), a Commando since 17 years, had seen active service with No. 12 Commando in enemy occupied Norway, also saw action with 3 Commando when we had previously invaded from the sea the toe of Italy, and that, together with my experience with 6 Troop on the ridge, convinced me that come the dawn, our terrific Commando leaders of all ranks, would fight it out to the bitter end.

I was 18 years of age, been a soldier since 16yrs (lied about my age), a Commando since 17 years, had seen active service with No. 12 Commando in enemy occupied Norway, also saw action with 3 Commando when we had previously invaded from the sea the toe of Italy, and that, together with my experience with 6 Troop on the ridge, convinced me that come the dawn, our terrific Commando leaders of all ranks, would fight it out to the bitter end.

At that stage of my war I was as yet still a ‘Trooper’ and Commando ‘follower’ adapting to whatever action our superb ‘Commando Leaders’ decided to take, in whom I had developed complete trust.

Accordingly, I considered, come the enemy dawn attack, I would probably be looking at my own death in the face. At stand to in my slit trench that night, my thoughts inevitably turned to my family back home, all of whom, including myself, believed in the Christian faith, and the strong possibility of they receiving the dreaded 2nd World War Telegram informing them I had been ‘Killed in action’. I said a few silent prayers in that respect to my parents, brother and sister.

After a long night, watching my front on ‘Stand-to’ the unexpected happened. Tony Turner, our Troop Sgt Major appeared instructing that I fix my bayonet, take all my equipment and arms with me and make my way silently as possible to the rear of the ridge – then moved on to the next slit trench, presumably with the same message.

At that time, unknown to me (or to the others of 6 Troop) Captain Hopson [more....] of 3 Cdo, together with his batman, had previously succeeded in finding a gap in the enemy lines surrounding us, made their way to Termoli to report to Commando Brigade HQ thus (Peter Young’s book ‘Storm From the Sea’ refers): “he explained 3 Cdo was surrounded on three sides by enemy at fifty to a hundred yards. It was evident that unless they were withdrawn before dawn, they would inevitably be annihilated”. Captain Hopson was then ordered to return to our ridge and lead 3 Cdo back to Termoli.

When I arrived at the back of the ridge I saw all our wounded lined up in single file, a few on stretchers, and the majority on blankets for the wounded to be carried by Commandos grasping firmly each corner of the blanket. Orders were being whispered so as not to alert the enemy. We lined up in single file with the wounded and moved off as silently as possible to make our way through the gap in enemy lines to withdraw to Termoli. If attacked we would respond accordingly. Immediately in front of me was a severely wounded Commando, semi-conscious, being carried on a blanket his body hunched up in considerable pain judging from the sounds he was making, which I felt certain would soon alert the enemy. That did not happen, as my next strong memory is of us arriving in the streets of Termoli which were filled with steel helmeted British troops, who it transpired were an infantry battalion of 32 Irish Brigade. They were put ashore from a troop ship that night as re-enforcements in readiness for the expected dawn attack by the German Panzer Division. As we carried on in single file, carrying our wounded, fully armed as a fighting unit, foot-slogging it past those fresh British troops, murmurings came to my ears from their midst, clearly saying “Well done Commandos, well done” over and over again. I presumed they must have been made aware of 3 Commando’s performance holding on to the ridge, where I personally had experienced, at different times, almost every known human emotion. As a result of those impromptu unexpected compliments from British soldiers, just for a moment or two, I felt ridiculously proud. 3 Commando were put in reserve at Termoli Railway Station, we of 6 Troop ended up in the railway station’s large buffet (no sign of eats – I did look) with its sizable glass windows in smithereens all over the floor, where we laid our weary backs hoping to snatch a cat-nap.

Dawn broke with enemy aircraft bombing the railway station and we were immediately on Stand-to, in reserve, by the railway tracks, with Jerry Spandau machine gun fire coming through in our direction. The other units at Termoli were front line of defence; in this renewed Panzer Division attack by tanks and infantry, we of 3 Commando took up a second defence line in the outskirts of the railway station being still in reserve. Then a most welcome sight – Canadian tanks in numbers and they seemed in a hurry appeared from the south, positive proof that the remainder of the Eighth Army 78th Division, stranded on the wrong side of the Biferno River, had finally made it across with Canadian tanks leading the way. The Royal Engineers having performed brilliantly getting pontoons over the river despite all the severe flooding of that water obstacle together with air attacks by Luftwaffe aircraft.

Reinforced by the rest of the 78th Div from the south together with RAF rocket firing Typhoons which appeared in the skies taking on enemy tanks, an exhilarating spectacle to behold. That last day was one hell of a battle with every gun, mortar, tank, aircraft, multi small arms fire, putting up overwhelming fire power until finally the 16th Panzer Division cleared off for good. The battle for Termoli and its deep water harbour having been won.

Colonel Durnford-Slater DSO & Bar wrote in his post war book “Commando”:- “Monty (General Montgomery) was delighted we had secured and held Termoli for him. The Commando Brigade’s action had helped the Eighth Army forward and had saved him from having to fight for the line of the Biferno River. It had also secured a useful harbour next to the front line where men and supplies could be landed. It had been a very near thing.”

Post script – 3 Commando’s stubborn resistance for some 36 hours on that strategic ridge (with their much reduced strength for the Termoli operation numbering 174 Commandos) delayed considerably the Panzer Division’s ultimate objective of a full blown attack to capture Termoli town and deep water harbour. This delay allowed the bulk of 78th Div, marooned on the other side of the Biferno River, the time to surmount the watery obstacle and get through to us at Termoli, also for air support by rocket firing Typhoon aircraft to be organised. The casualty rate for 3 Commando defending that ridge was surprisingly light, with 8 killed or missing, 28 wounded. Our casualties of course could well have been a lot worse – but in war we were always grateful for small mercies.

Termoli the aftermath:-

Captain John Reynolds – 3 Commando’s 6 Troop Commander, sustained serious wounds – awarded “Military Cross”.

Lieutenant John Alderson – 3 Commando, 6 Troop took over command of 6 Troop once Captain Reynolds finally agreed to be removed to the rear, awarded “Military Cross”.

Corporal Harrison – 3 Commando 2 Troop, but in 6 Troops lines over seeing Vickers machine gun crew of 78th Div – promoted to Officer Rank of Lieutenant, and posted to No. 6 Commando.

Trooper Jack Leech – 3 Commando, 6 Troop Bren Gunner – promoted to Sergeant no commissioned rank – awarded “Military Medal”.

Sergeant ‘Nobby’ Knowland – 3 Commando, 6 Troop, my sub-section Sergeant – promoted to Officer Rank of Lieutenant and posted to No.1 Commando in Burma Far East. On 31st January 1945, Lieutenant (‘Nobby’) George Arthur Knowland of No.1 Commando at battle for Hill 170, Kangaw, Burma, awarded posthumously VICTORIA CROSS in circumstances of outstanding, incredible heroic courage.